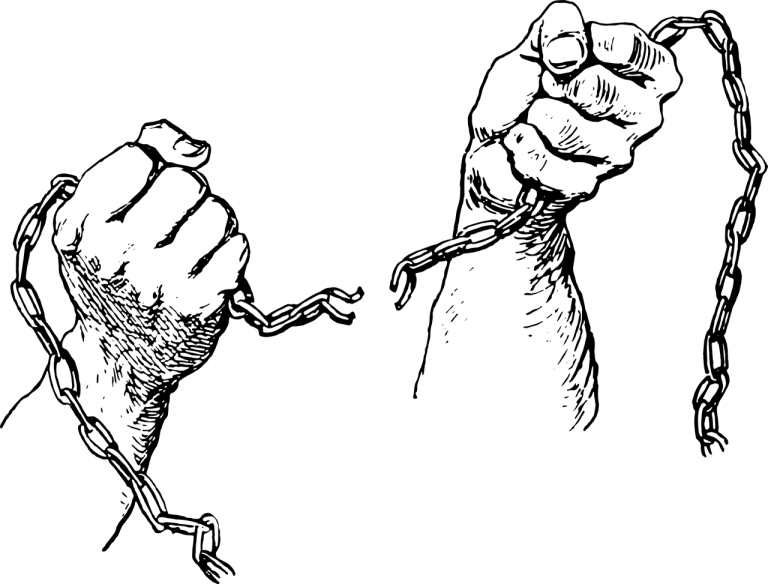

Emancipation

On January 1, since 1863, we celebrate the Emancipation Proclamation in the United States.

There is a long history of enslaved freedom seekers in the Americas.

On December 5, 1492, Christopher Columbus anchored in Española (Little Spain), the second largest island of the West Indies. The island is now known as two separate nations: the Spanish-speaking Dominican Republic to the east and the French/Haitian Creole-speaking Haiti to the west.

Jean-Jacques Dessalines proclaimed Haiti, then known as St-Domingue, independent from the French on November 29 1803, making it the first time former slaves became an independent nation.

When the slaves of St-Domingue revolted and killed their masters, the plantation owners in the South of the United States became afraid that their own slave would get ideas about freedom and band together in rebellion. They weren’t wrong.

On their Sunday evenings, in their own worship services, the slaves sang about freedom. Nat Turner, a black minister from a Virginia plantation, traveled around nearby villages preaching and preparing the slaves to rise and fight. On August 31st, 1831, starting with seven men and building up to forty, the slaves moved from plantation to plantation, killing their masters and their families with axes and guns. They killed over fifty whites. Whites armed themselves and went after the rebels. As a result, over one hundred and twenty innocent black men and women were murdered.

Two months later, Nat Turner was captured. Before they hung him, however, his story was written and published by his lawyer, Thomas Gray, as The Confessions of Nat Turner, Leader of the late Insurrection in Southampton, Virginia.

The consequences of this rebellion made life harder for the slaves in the Southern States. Some of the new restrictions were laws passed keeping slaves from meeting together in groups of over three, black ministers were kept from preaching to their congregations, and anyone who taught a slave to read and write would be punished by a year in jail. It affected Free African-Americans as well, because they were not allowed to own guns or to meet together at night unless three white men were present at all times.

Although rebellions were unsuccessful in the Southern United States, slaves continued to seek freedom. Many, often with the aid of the underground railroad, escaped to Canada, Mexico, Spanish Florida, Indian territories (such as the Black Seminole), the West, the Caribbean islands and Europe.

In colonial America, runaway slaves were called Maroons. For over four centuries, Maroons formed communities, escaping plantations from Brazil to Florida and from Peru to Texas. Usually called Palenques in the Spanish colonies and Mocambos or Quilombos in Brazil, they ranged from tiny bands that survived less than a year to powerful states encompassing thousands of members and lasting for generations.

Maroons found San Basilio de Palenque over two hundred years before Colombia achieved independence from Spain. In 1713, the Spanish crown issued a Royal Decree that officially freed the people of the Palenque from slavery. It has preserved the culture of those who fled a life of slavery in colonial times intact in Colombia. It’s a unique place, famous for its culture, language, gastronomy and its history. UNESCO declared San Basilio de Palenque a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2005.

Here is a link to San Basilio Palenque:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BUaINJAyzu4

References:

https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/runaway-slaves-latin-america-and-caribbean

https://www.nps.gov/subjects/undergroundrailroad/what-is-the-underground-railroad.htm